The 14-percent advantage of eating little and then a lot: Putting it in practice

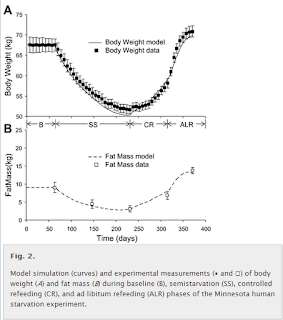

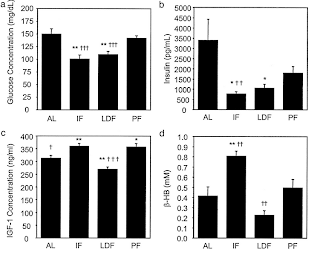

In my previous post I argued that the human body may react to “eating big” as it would to overfeeding, increasing energy expenditure by a certain amount. That increase seems to lead to a reduction in the caloric value of the meals during overfeeding; a reduction that seems to gravitate around 14 percent of the overfed amount. And what is the overfed amount? Let us assume that your daily calorie intake to maintain your current body weight is 2,000 calories. However, one day you consume 1,000 calories, and the next 3,000 – adding up to 4,000 calories in 2 days. This amounts to 2,000 calories per day on average, the weight maintenance amount; but the extra 1,000 on the second day is perceived by your body as overfeeding. So 140 calories are “lost” . The mechanisms by which this could happen are not entirely clear. Some studies contain clues; one example is the 2002 study conducted with mice by Anson and colleagues ( ), from which the graphs below were taken. In the graphs above AL refers